At this year’s German Library Congress in Bremen, several of my colleagues gave readings from books they had written. Unfortunately, I am not a writer. However, I did experiment with using AI to ‘write’ a short story in the style of Edgar Allan Poe with a library theme.

I am not sure if it’s a literary masterpiece, but I am happy to share it here.

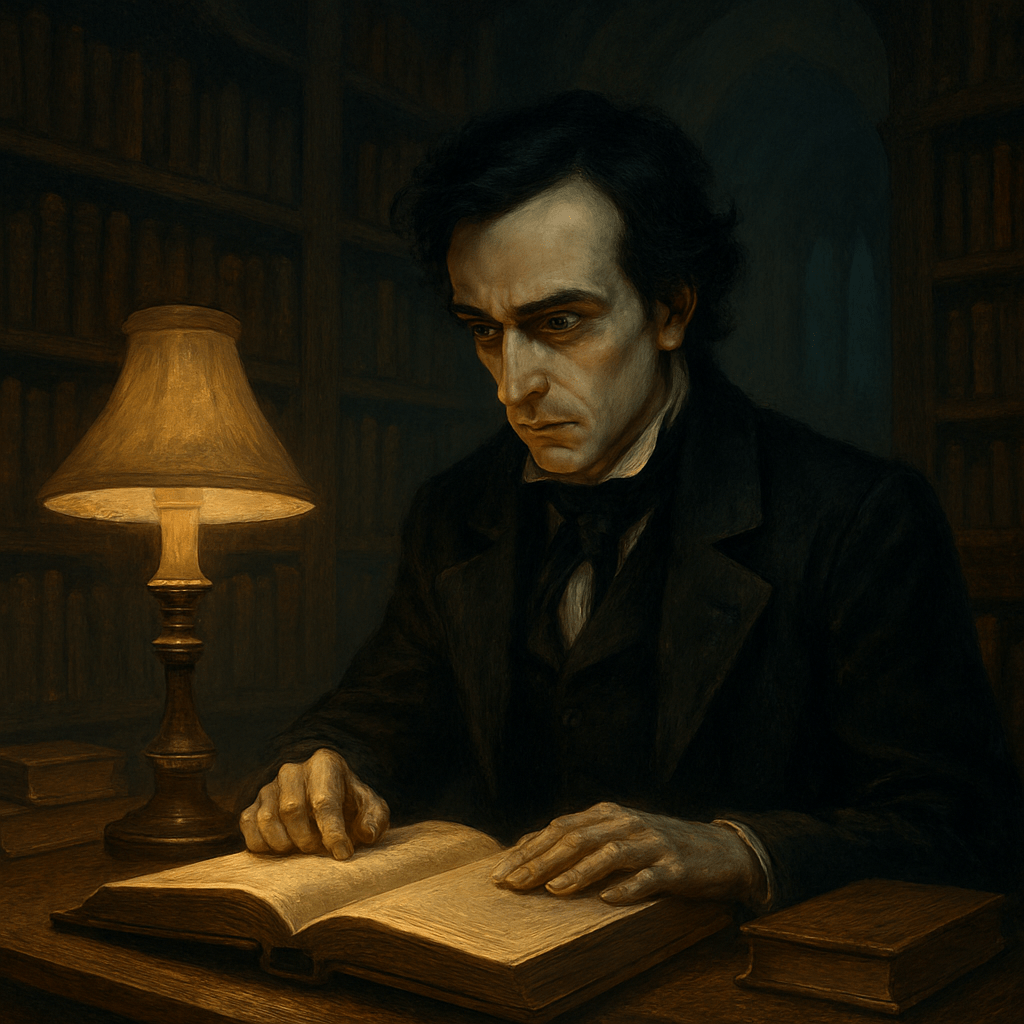

The Luminous Thirst

True!—nervous—very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses—not destroyed—not dulled them. Above all was the sense of sight acute. I observed—oh, how minutely I observed!—every shadow, every gleam, every particle of dust that danced in the accursed sunbeams of that library. For it was the light—the light!—that would prove to be both revelation and damnation.

You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded—with what caution—with what foresight—with what dissimulation I went to work! Never before had I been so acutely aware of the terrible knowledge that dwelt within those leather-bound volumes, the secrets that men were not meant to uncover, the truths that should have remained buried beneath centuries of deliberate ignorance.

It was upon a grey October morning that he first appeared in my sanctuary, this pale stranger who would become the architect of my damnation. Tall as a cathedral pillar and white as winter moonlight, he moved through the reading room with an otherworldly grace that set my very soul to trembling. His hair was dark as a raven’s wing, his eyes the colour of arctic ice, and upon his lips played a smile of such cold beauty that it might have been carved by some ancient, malevolent sculptor.

Never—and I cannot emphasise this point with sufficient force—never did I see him cast a shadow.

For three weeks I observed him with the intensity of one studying a rare and potentially dangerous specimen. He would arrive each morning precisely at dawn, carrying with him a curious leather satchel that clinked softly as he walked. From this bag he would withdraw strange devices—mirrors, glass prisms, and what appeared to be concentrated gas lanterns of unusual design. These he would arrange around his chosen table, always positioning himself beneath the largest skylight, always facing east toward the rising sun.

During the hours of brilliant illumination, he seemed to possess an energy, a vitality that was almost superhuman. His movements were swift and sure, his voice carried clearly across the reading room, and his pale skin seemed to glow with an inner radiance that hurt the eyes to look upon directly. But as afternoon shadows began to lengthen, I observed a gradual transformation that filled me with inexplicable dread. The vitality would slowly drain from his features, his movements would become sluggish, and that terrible pallor would increase until he appeared as one already half-consumed by death.

Always—always—he would depart before the sun touched the horizon, gathering his curious apparatus with frantic haste and fleeing as if pursued by the very demons of hell. Yet sometimes—and here my voice trembles as I recall it—I would glimpse him through the windows during his retreat, huddled beneath a street lamp or frantically lighting one of his portable devices, consuming light as a drowning man consumes air.

It was during my careful cataloguing of his research that I discovered the true nature of his scholarly pursuits. Hidden among the returns upon my desk, I found the volumes he had been consulting: “De Sanguinibus Luminosis,” “The Daylight Hunger,” “Accounts of the Solar Dead.” Each tome described creatures of legend—beings that sustained themselves upon human blood but required the light of the sun to maintain their unholy existence.

Vampires. But not the creatures of folklore that fled from holy light—no, these were monsters that depended upon it, that grew weak and died in darkness, that had haunted the daylight hours of humanity since time immemorial.

Then came the morning that confirmed my darkest suspicions and set in motion the terrible events that would follow.

Young Patterson burst through the oak doors of the rare manuscripts section with a shriek that seemed to pierce the very foundations of my soul. I found him backing away from the reading nook where our most precious medieval texts were housed, his face white with such terror as I had never before witnessed in one so young.

There, sprawled upon the cold stone floor like some grotesque offering to an unspeakable deity, lay the mortal remains of Dr. Cornelius Van Der Berg, late professor of medieval studies and rival researcher of the same obscure texts that had drawn my pale visitor.

His flesh had taken on the pallor of ancient parchment, drained of every drop of that vital essence which we call life. Upon his throat were two small wounds, perfectly round, from which his life’s blood had flowed as wine from a punctured cask. But what struck me as most singular was the expression upon his countenance—his eyes, wide with final terror, stared not into the darkness of death, but toward the eastern windows where the morning sun had begun its eternal ascent.

The constabulary arrived within the hour. Inspector Blackwood examined the scene with methodical precision and pronounced his verdict: “Exsanguination. Complete drainage of blood. This would have taken many hours—the victim was kept alive and conscious throughout the process.”

Many hours! The words echoed through my mind like the tolling of a funeral bell. Dr. Van Der Berg had suffered through the entire night while some fiend sustained itself upon his torment. But what manner of creature could perform such a deed and then vanish with the dawn?

That very afternoon, my pale visitor returned.

I watched from behind the circulation desk as he moved through the main reading room, but something had changed. Where before he had moved with careful deliberation, now there was urgency in his step, desperation in his movements. He positioned himself beneath the largest skylight, but his usual apparatus remained in his satchel. Instead, he gazed about the room with the air of one seeking something specific—something he had not found in poor Van Der Berg.

“Miss Ashwood,” he called softly, and I felt my blood turn to ice at the sound of my name upon his lips.

I approached with trembling steps, noting how the afternoon sun seemed to pool around him like liquid gold, casting no shadow upon the floor.

“I understand there was some… unpleasantness here this morning,” he said, his voice carrying that same musical quality that had first drawn my attention.

“A death,” I managed to whisper. “Dr. Van Der Berg.”

“Ah, yes. Poor Cornelius. He was… uncooperative.” The stranger’s smile revealed teeth too white, too sharp. “I had hoped to avoid such measures, but my kind grows desperate as winter approaches. Each day the sun grows weaker, the hours of light fewer. We must secure our survival before the dark season arrives.”

“Your kind?”

“We are the children of light, Miss Ashwood. We feed upon the crimson essence of life, but we cannot exist without the blessed radiance of the sun. In the old days, when men lived by candlelight and hearth-fire, we could sustain ourselves through the winter months. But now, in this age of gas and electricity, such weak illumination barely sustains us through a single night.”

His eyes fixed upon mine with terrible intensity. “Which brings me to the purpose of my visit. I require access to your restricted collection—specifically, the Vasiliev Manuscript.”

The name struck me like a physical blow. I knew that accursed tome—a medieval text describing the creation of artificial sunlight, concentrated solar essence that could supposedly sustain life indefinitely. It had been acquired by the university decades ago and locked away due to its dangerous alchemical formulas.

“The restricted archive requires special authorisation—” I began.

“Which you will provide,” he interrupted, sliding a prepared document across the desk. “Or I fear there will be further… unpleasantness. My brethren are not as patient as I.”

“Brethren?”

“A dozen, perhaps more. They arrive tonight with the darkness, seeking what I have failed to obtain peacefully. They will search every corner of this building, drain every soul within these walls, until someone provides them with what they seek.”

The threat was clear, but as I stared at the authorisation form, a terrible realisation crept over me.

“The restricted archive,” I said slowly, “has no windows. No natural light.”

For the first time, I saw uncertainty flicker across his perfect features.

“Artificial lighting will suffice,” he said, but his voice lacked conviction.

“The building’s electrical system is old,” I continued, my courage growing with understanding. “Power failures are common. And the archive—it’s in the basement, surrounded by stone walls three feet thick. If the lights were to fail…”

Sebastian—for that was the name I had glimpsed upon his false credentials—took a step backward, and I saw fear bloom in those arctic eyes.

“You wouldn’t dare,” he whispered.

But I had already begun to move. With steady hands, I walked to the main electrical panel behind the circulation desk. The building’s lighting was controlled from this central point—a design flaw the university had always intended to correct but never found the funds to address.

“Wait,” Sebastian cried, his composure finally cracking. “You don’t understand what you’re doing. When night falls, they will come. If I’m not here to lead them to the manuscript, they will kill everyone in this building searching for it.”

“Then I suppose,” I said, my hand hovering over the master switch, “we shall have to trust in the darkness.”

I threw the switch.

Every light in the building died instantly, plunging the library into the grey gloom of approaching dusk. The emergency lighting flickered briefly, then failed completely—a consequence of the building’s ancient electrical system that the university had never found the funds to properly update. The library was now completely dependent upon the fading natural light filtering through the windows.

Sebastian’s transformation was immediate and terrible. His pale skin became translucent, revealing the dark network of veins beneath. His eyes sank into his skull, and his breathing became a ragged wheeze. He collapsed to his knees, reaching toward me with fingers like white bone.

“Please,” he gasped. “The others… they’ll sense my death… they’ll come in force…”

“Let them come,” I said, though my voice trembled with the magnitude of what I had done. “They’ll find nothing but darkness waiting for them.”

As the last rays of sunlight faded from the windows, Sebastian’s death rattle echoed through the silent halls. But even as his body crumbled to dust, I heard them—footsteps on the roof, scratching at the windows, the sound of glass breaking in distant rooms.

They had come, as he had promised. But they had come to a building shrouded in perfect darkness, their supernatural senses dulled by the absence of the light they craved, their strength sapped by the very environment they now found themselves trapped within.

Through the long hours of that terrible night, I heard them searching, growing weaker with each passing moment. Some fell silent near the windows, where the faintest starlight might have sustained them briefly. Others I heard scratching desperately at the walls, seeking any crack through which light might enter. Their whispers grew faint, then fainter still—”Light… light… blessed light…”—until they faded into the eternal silence of the grave.

By dawn, all was silent. Silent!—but not peaceful, never peaceful, for in that silence lay a horror more profound than any scream.

But when the sun rose, bringing blessed illumination back to the world above, I made a discovery that fills me with equal parts wonder and horror and madness—yes, madness! For the darkness had changed me, transformed me, remade me in its own image, just as the light had sustained them. Where they had fed upon blood and sunlight, I had consumed shadow and silence and the very essence of the void itself. Where they had grown weak in darkness, I found strength—such strength!—in the all-embracing night.

I had become their opposite—their perfect antithesis.

Now I sit here in my chosen realm of eternal night, having severed every wire, sealed every window, blocked every source of illumination save for the single candle by which I write these words. The Vasiliev Manuscript lies hidden in the deepest vault of the archive, where no light—natural or artificial—will ever touch it again.

The vampires return each day, as they must. I hear them gathering outside with the sunrise, their strength renewed, their hunger sharp. They scratch at the walls, seeking entry to my sanctuary of shadows. But they cannot enter here, any more than I can venture into their domain of light.

We are bound in perfect opposition—they in their blazing realm above, I in my midnight kingdom below. They hunger for the manuscript that could free them from their dependence upon the sun. I guard it with a vigilance born of shadow and sustained by darkness.

Listen! Do you hear that scratching at the windows? They have returned with the dawn, and their need grows desperate as winter approaches. Soon the days will grow short, the sun weak and pale. They will become frantic in their search, reckless in their hunger.

But let them claw at the walls until their fingers bleed light instead of crimson. Let them press their pale faces against the glass, drinking in the precious rays that sustain them, forever denied entry to the darkness where their prize lies hidden. The manuscript they seek lies in the deepest shadow, where I have hidden it beyond the reach of any illumination.

For I have learned the secret that eluded them: true power lies not in feeding upon light or shadow, but in choosing one’s darkness deliberately, embracing it completely, and making it one’s kingdom.

They are slaves to the sun.

I am sovereign of the shadow.

And in this eternal war between light and darkness, between the luminous thirst above and the consuming void below, there can be neither victory nor peace—only the perfect, terrible balance of opposing hungers.

The candle gutters now. Soon even this feeble flame will die, and I will be complete in my transformation. They will scratch and claw above while I rest in perfect darkness below, guardian of the one thing they need, prisoner of the one thing they fear.

Let them thrive in their brilliant prison.

I have found my heaven in the dark.

Leave a Reply